The Enshittification of Digital Services

Explore how the deterioration of digital services reflects on the design of digital applications.

In a linguistic beat, the Macquarie Dictionary crowned "enshittification" its 2024 Word of the Year. Coined by Cory Doctorow, the term captures the gradual deterioration of services –mainly digital platforms– by prioritizing profits over user experience and societal benefit. This recognition highlights the challenge of transforming digital products from a purely extractive model to one that genuinely delivers sustainable value to users.

The story of digital companies follows a familiar pattern of transformation. The prelude tells the tale of going above and beyond for their users. They distinguish themselves by delivering the best solution to users' needs, which is more convenient, functional, and cost-effective than existing alternatives.

In the following chapter –the growth phase– startups focus on expanding their user base. They attract newcomers by offering generous incentives, awards, free features and special deals. With more users, the services flourish and often achieve significant market presence.

The pivot shift: The new company, now with shareholders, open capital, and market pressure, aggressively monetizes its services by introducing ads, paid features, or subscriptions. Eventually, the services prioritize maximizing revenue (often for shareholders), leading to degraded services, aggressive ads, and anti-consumer practices.

These manipulative tactics, the deceptive patterns, are to stimulate revenue-generating user behaviors. The manipulation can be a simple free trial period that automatically converts to a paid subscription. Users often end up paying for unwanted services simply because the cancellation process requires effort –sometimes patience– and they're unwilling to expend.

From a digital business perspective, enshittification means short-term profit-seeking overriding long-term user retention. Companies like Facebook, Uber, and Amazon initially provided huge value, but as competition decreased, they began to extract more from users and partners (e.g., higher ad prices, algorithm manipulation). Think of Twitter, a once helpful and often enjoyable microblogging platform that has twisted into what many define as a post-truth swamp.

Digital services increasingly push users into subscriptions or closed ecosystems, limiting choice while increasing dependency. Companies gradually extract more value once users are locked in while offering less service. This trend has led to growing concerns about digital monopolies and exploitative business models. Governments, to protect the users, are increasingly scrutinizing digital services and tightening regulations, leading to antitrust cases and policy interventions, emphasizing the need for fair competition and consumer protection in digital markets.

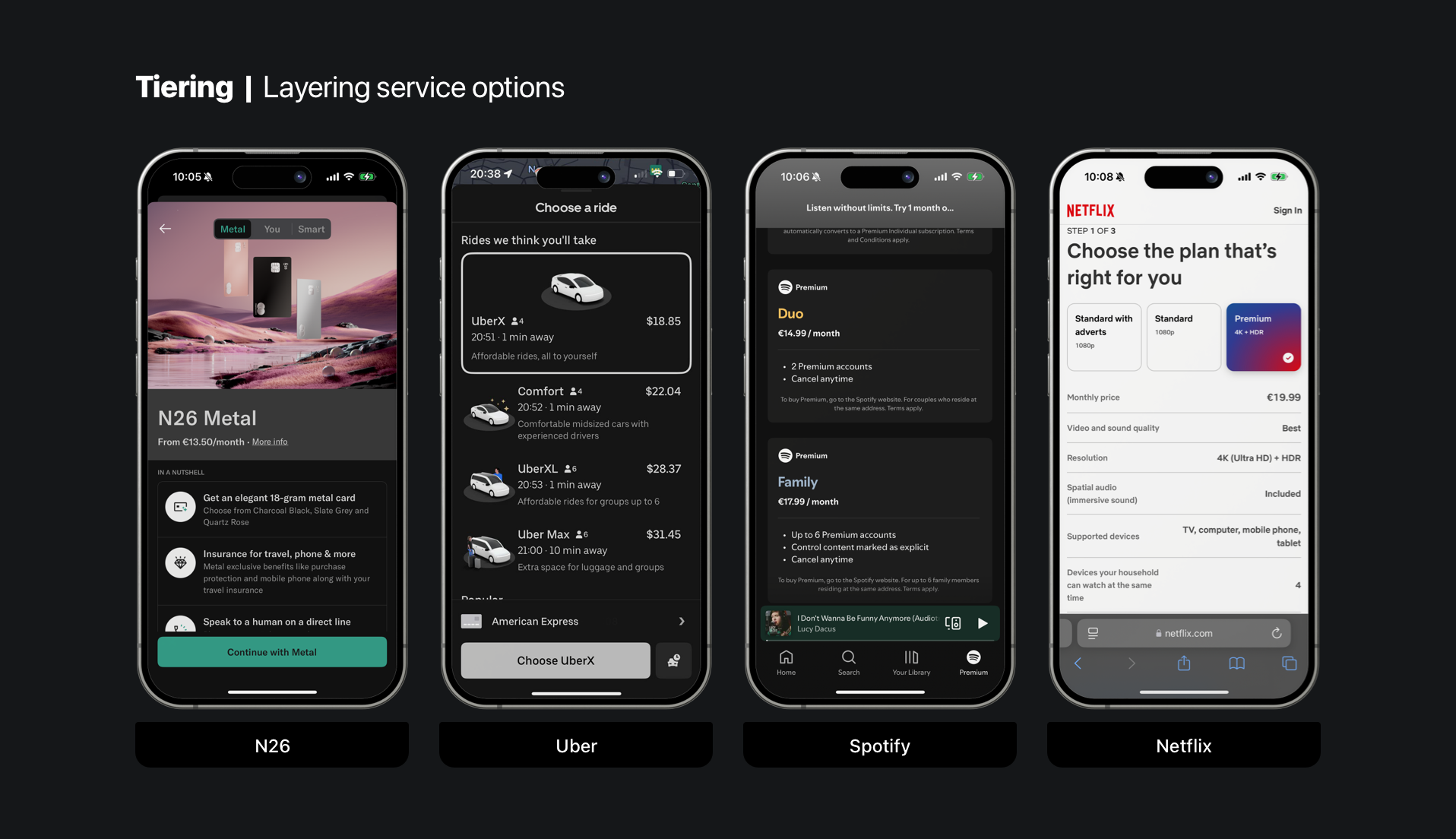

The Tiering Strategy

The process of enshittification generally begins with tiering, offering different pricing for different layers of service. This strategy can be positive, allowing users to choose a plan that better fits their needs and budget. However, a darker reality emerges when the cheapest packages deliberately offer inferior products.

Uber's tiering system, for example, ensures that the standard plan—the cheapest—often has an old car or is not comfortable enough to be in the premium listing. The enshittification comes when it is not about making it better for the ones who pay more but penalizing those who pay less.

Netflix followed a similar path with its 4K package, charging three times the price for access to the same catalog. Not all content is available in 4K, making the upgrade less about added value and more about artificially restricting quality to push users toward higher-priced plans.

The Subscription Trap

Amazon's Prime started as a one-day delivery subscription, offering convenience at a fixed price. Over time, Prime members began facing additional charges for the one-day delivery of some products or even buying extra to get the service once included in the subscription. Simple math: users pay more for the same service they enjoyed years ago.

Streaming services illustrate this shift. It began as an affordable alternative to cable or purchasing physical media—one platform with access to a vast content library. As the market expanded, new competitors emerged. Nowadays, to keep track of the hit shows, users need to subscribe to 3 or more different services. The available time to watch remains the same as before and users now juggle multiple platforms and several subscriptions to pay. Adding up the costs of streaming services, it often matches –if not more– than they once did on DVDs. But now, users don’t own anything.

Subscriptions provide regular, predictable revenue, making them a stable business model. However, problems arise when extra services are upsold, ads are introduced, and expensive tiers lock essential features behind paywalls previously included in the base package.

Research from EmailTooltester reveals another concern: canceling a subscription from major services is intentionally difficult. It can take up to 10 steps to cancel a subscription, discouraging users from opting out. Worse, almost two in three (65%) people continue paying at least three months of subscriptions for someone who has passed away.

Real-World Examples

Uber launched in 2009 with a straightforward concept: connecting drivers with passengers through a seamless app experience. It promised to revolutionize mobility by offering an efficient and modern way to get from point A to point B.

The initial strategy was simple: attract drivers with bonuses and rewards and users with free first rides. As Uber became essential and achieved near-monopoly status, enshittification set in. Fares increased, surge pricing was introduced, and driver compensation was reduced. Shifting the focus from user benefits to maximizing shareholder profits.

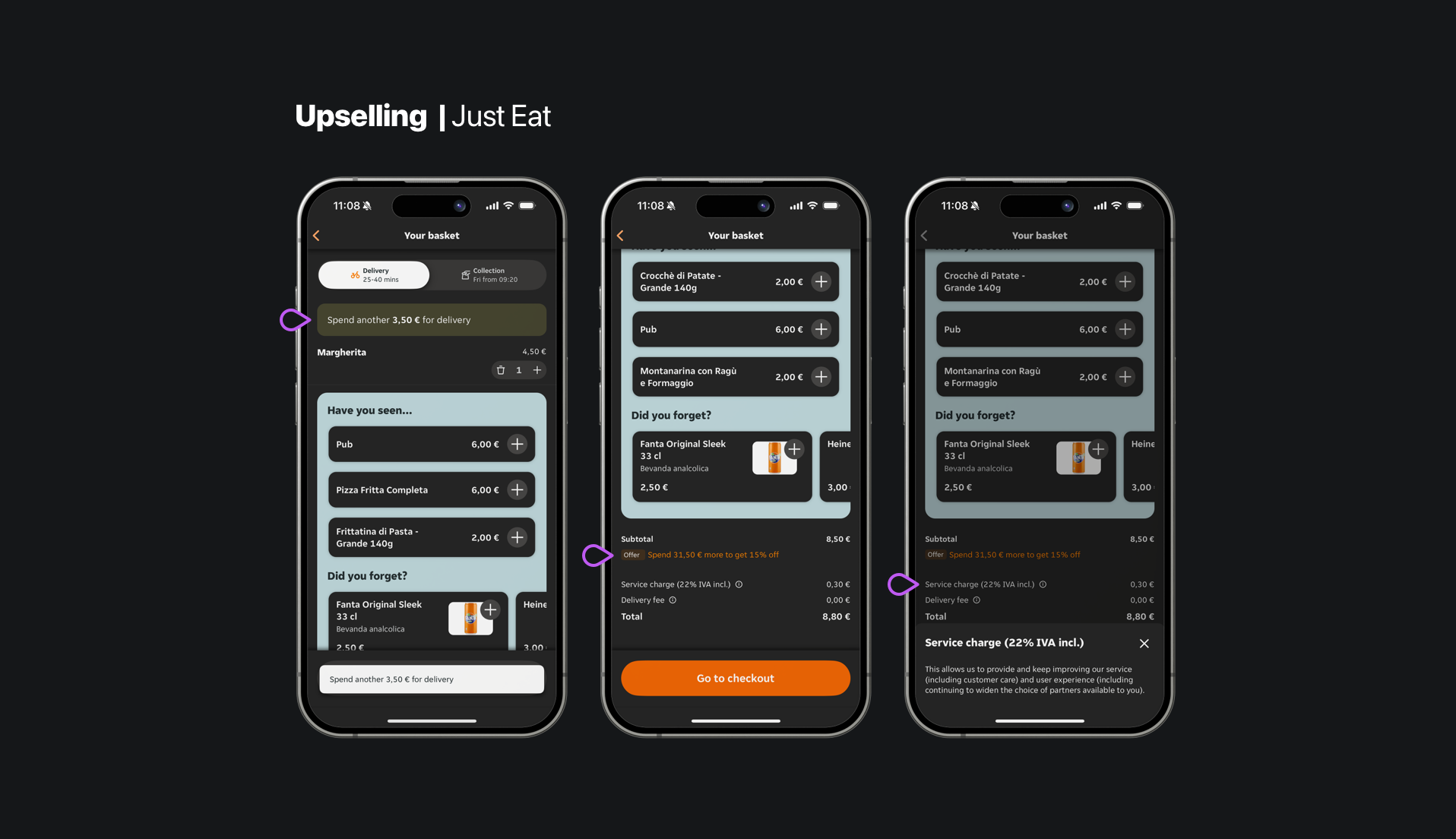

Just Eat has a similar story of being a convenient food delivery service and moving to a deceptive pattern platform. The app uses different tactics, providing similar enshittification, and nudging users to order more food. Selecting a product that falls below the minimum order value for free delivery offers an option to consume more. The delivery effort is the same – with or without many products – but now users are ordering more food, with a high possibility of food waste.

Now, the temptation to add more items to the basket and get a 15% discount in an order where the user is already buying more than the initial need. With or without the extras, a 22% service charge is included in the checkout. An extra to 'allow them to work to improve users' experience'. The fee is calculated by the total amount, including the extras the user added to get free delivery or discount. And don't forget, on top of this fee, there is the restaurant's fee for using the service.

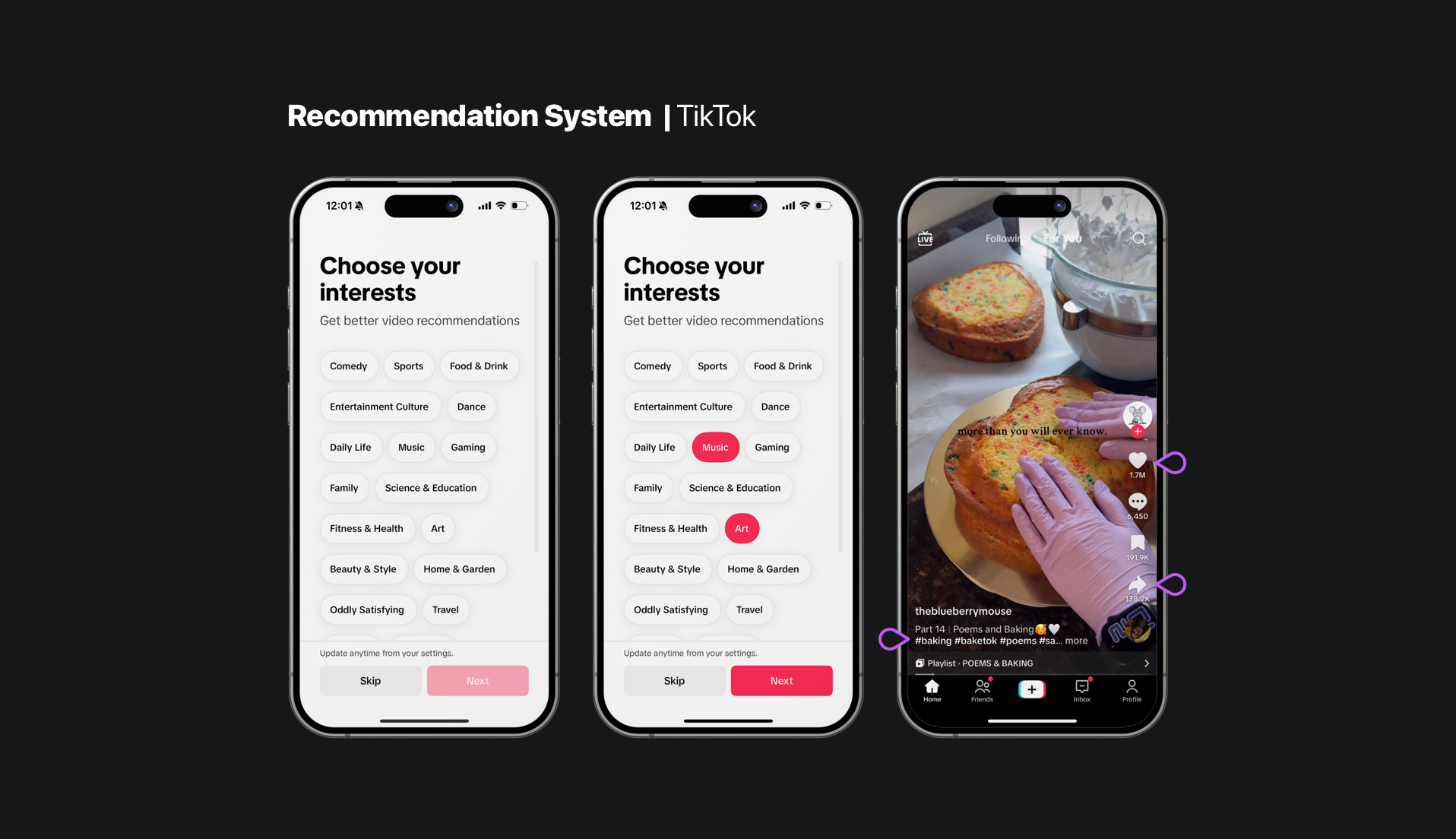

In the early days, TikTok was a success due to its powerful recommendation system. The app built a massive audience by delivering relevant content while attracting media companies and creators. Once the dominance was secured, its algorithm prioritized videos that maximized profitability. The focus was no longer on what users wanted to see but what the platform wanted them to watch.

Sustainable Strategies

To break the cycle of enshittification, digital businesses must adopt consistently user-centric models that generate sustainable revenue without compromising trust. Ethical advertising and fair subscription models should be the foundation, not an afterthought.

Transparency in algorithms is essential; content recommendations and search rankings should prioritize user value instead of monetization strategies. True success comes from creating long-term value rather than seeking immediate profits. The key is balancing between profitability, innovation, and genuine user satisfaction. Only then can digital services remain viable and valuable in the long run.